Protest Fields: A study of placeholders

-

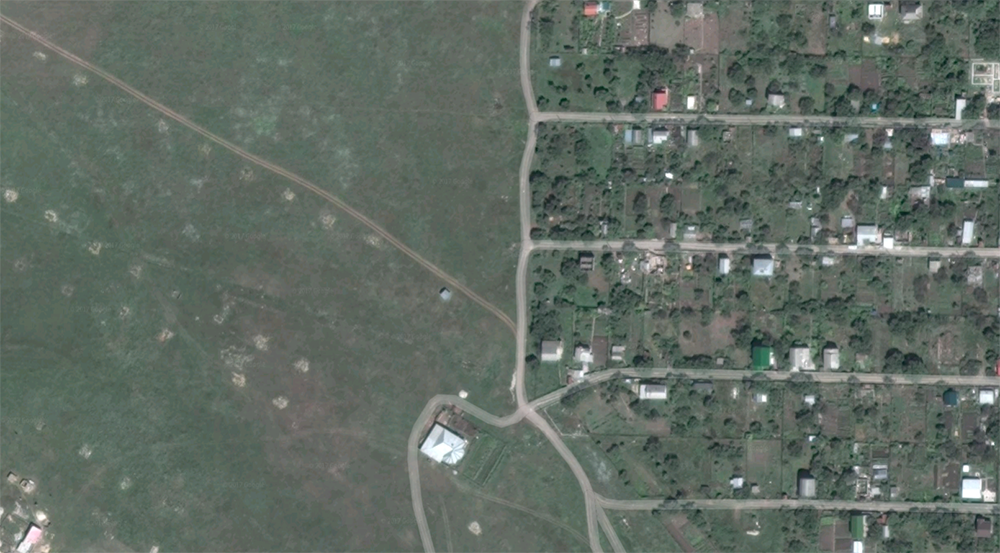

Little boxes on the hillside

Little boxes made of ticky tacky

Little boxes, little boxes

Little boxes all the same.

— Malvina Reynolds, 1962.

Little boxes on the hillside

Little boxes made of ticky tacky

Little boxes, little boxes

Little boxes all the same.

— Malvina Reynolds, 1962.